Material

unchanged

over time

Eternal material

Leather has always accompanied the history of humankind. A primordial material—resistant, mutable, capable of transformation—it crosses the centuries yet resists time. “Eterna” is a journey into this continuity: traces, gestures, techniques, and symbols that link past, present, and future.

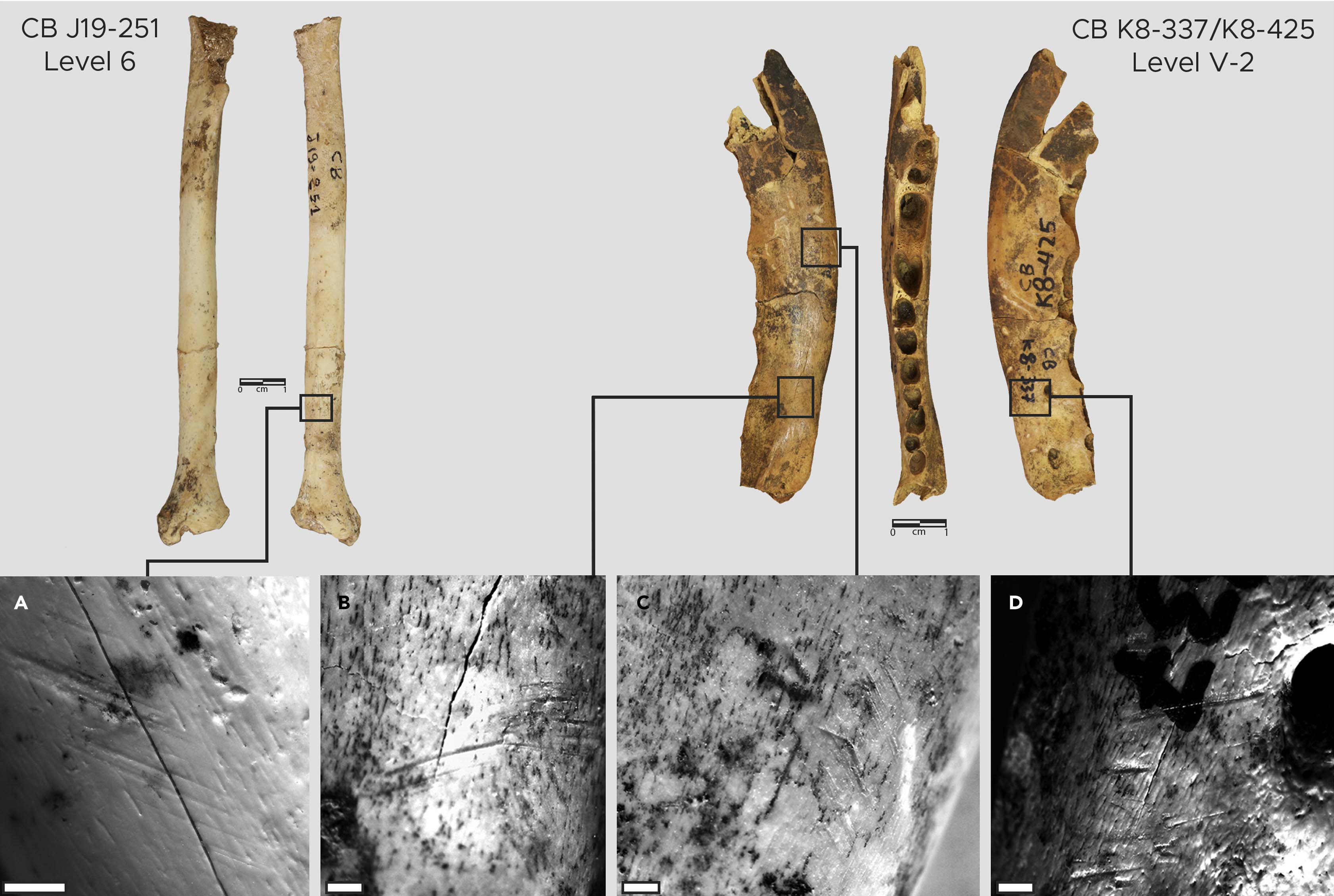

Prehistory

40,000 BC

Humans use animal hides to cover themselves, protect against the cold, and build rudimentary shelters. Early preservation techniques include drying, smoking, and the use of animal fats.

Ancient Era

3000 BC - 500 AD

Egyptians, Greeks and Romans develop primitive tanning techniques. Leather becomes a material for footwear, light armor, parchment, and tools.

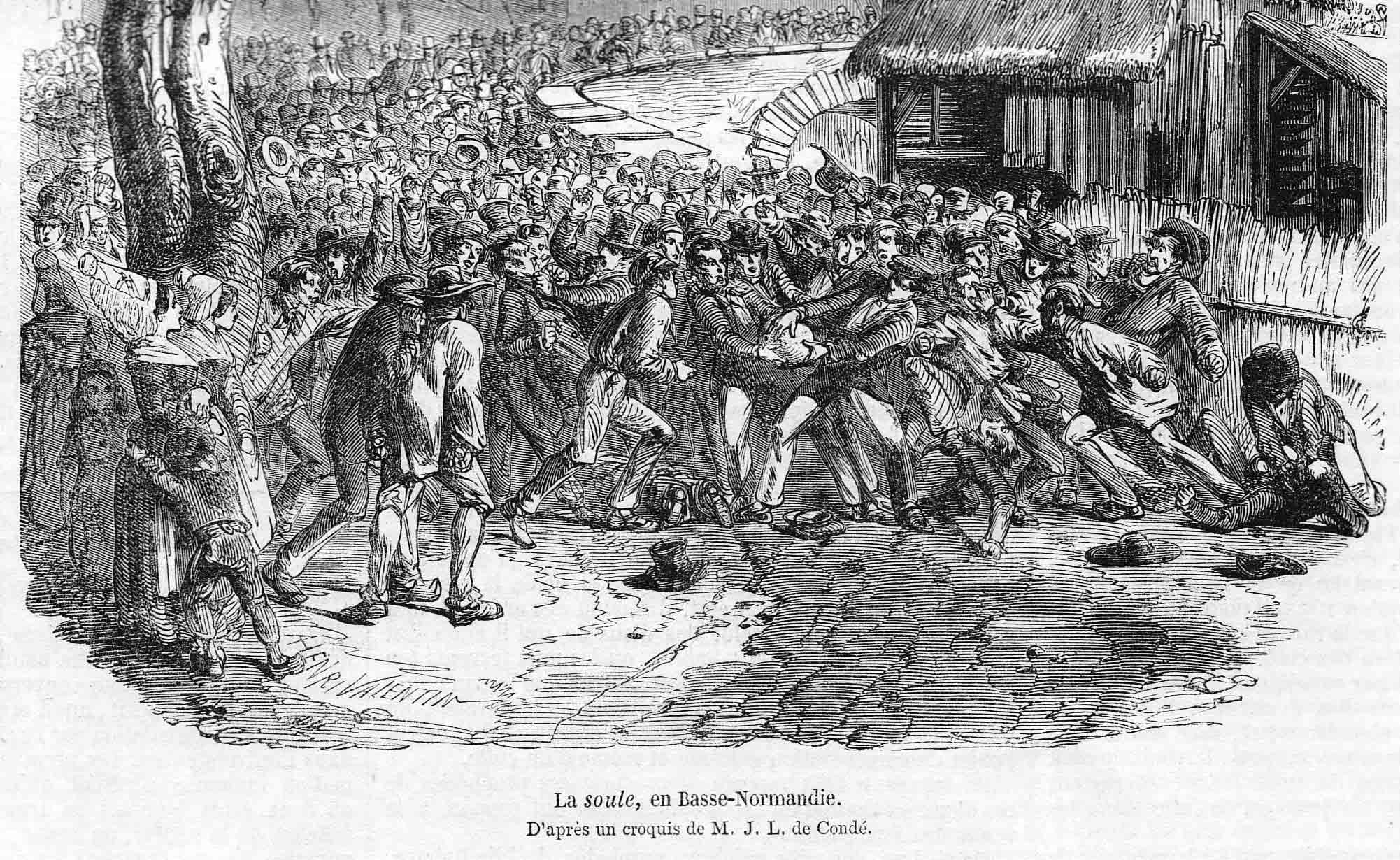

The Middle Ages

5th - 14th century

Tanners’ guilds emerge in European cities. Vegetable tanning with tannins extracted from bark and leaves becomes widespread.

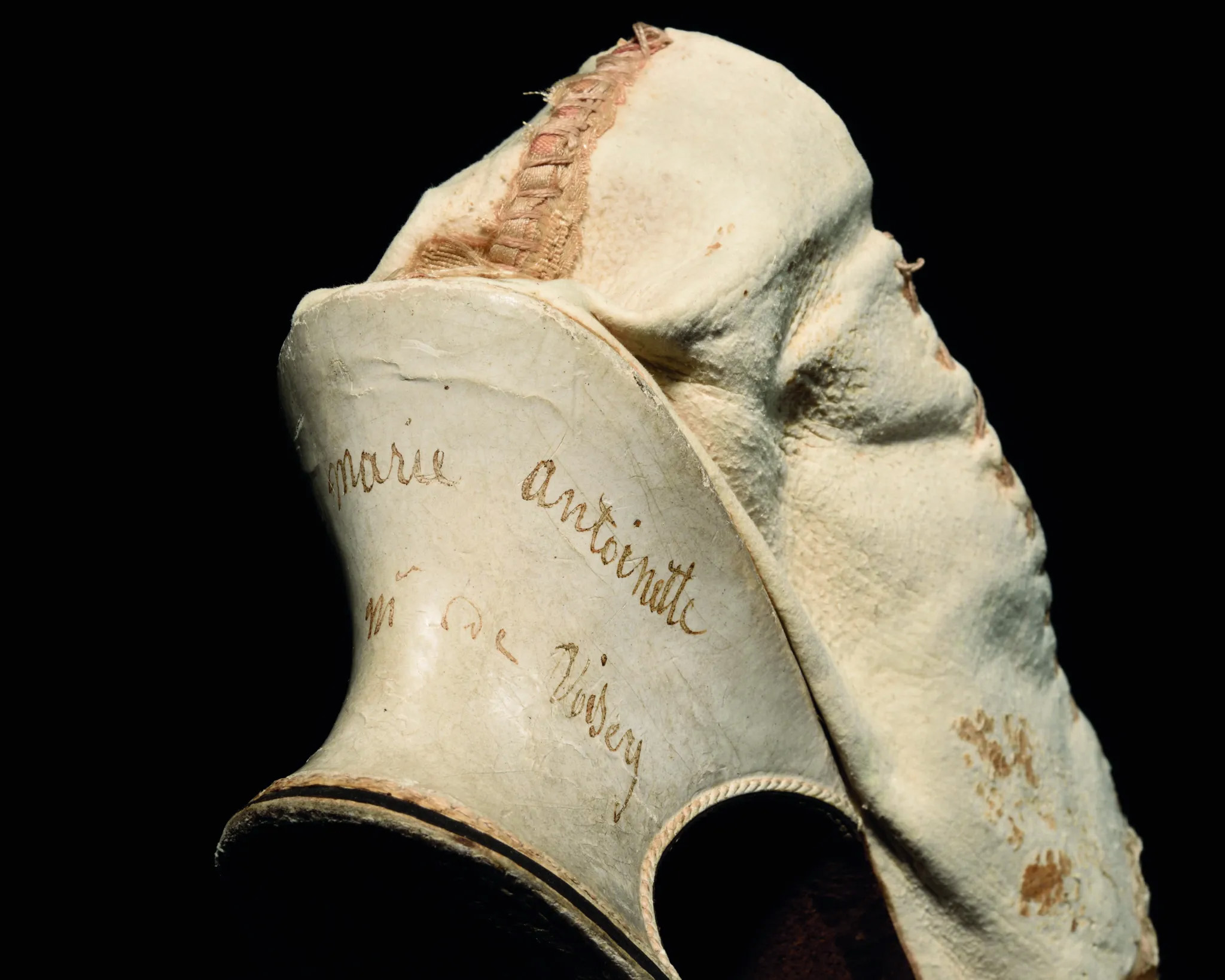

Renaissance

15th - 17th century

Leather is increasingly used for furnishings and luxury clothing. Florence and Venice become major centers for leather craftsmanship.

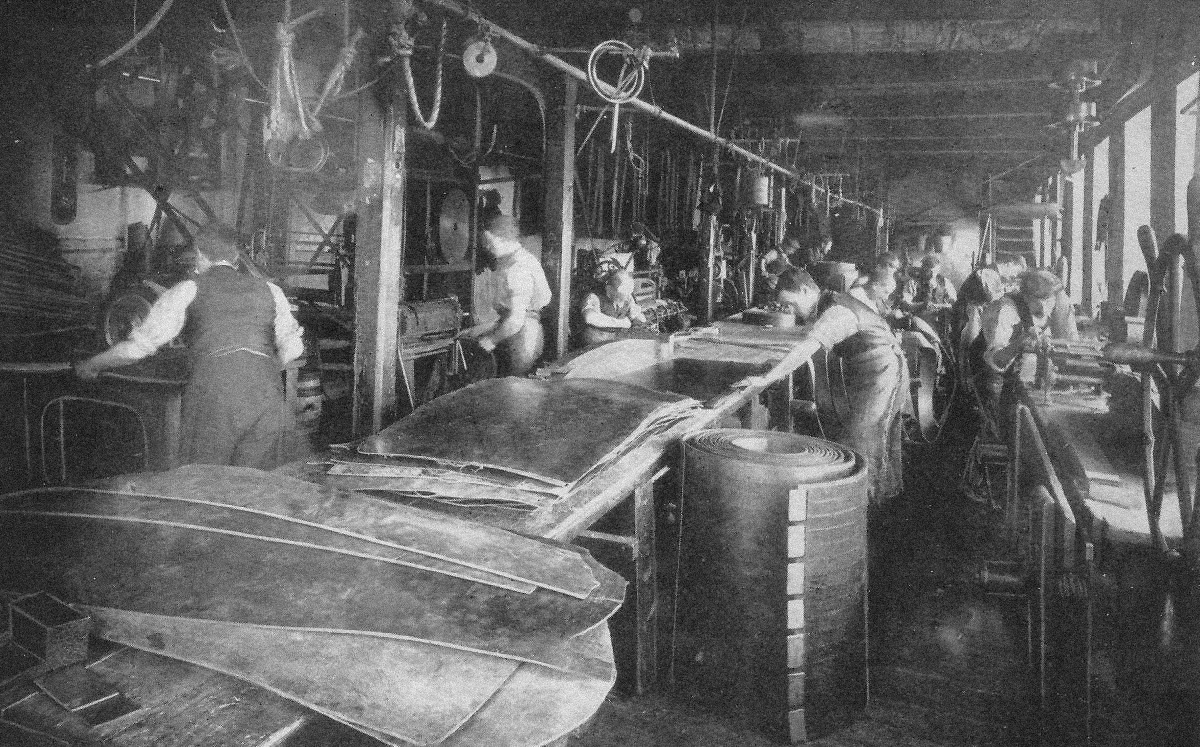

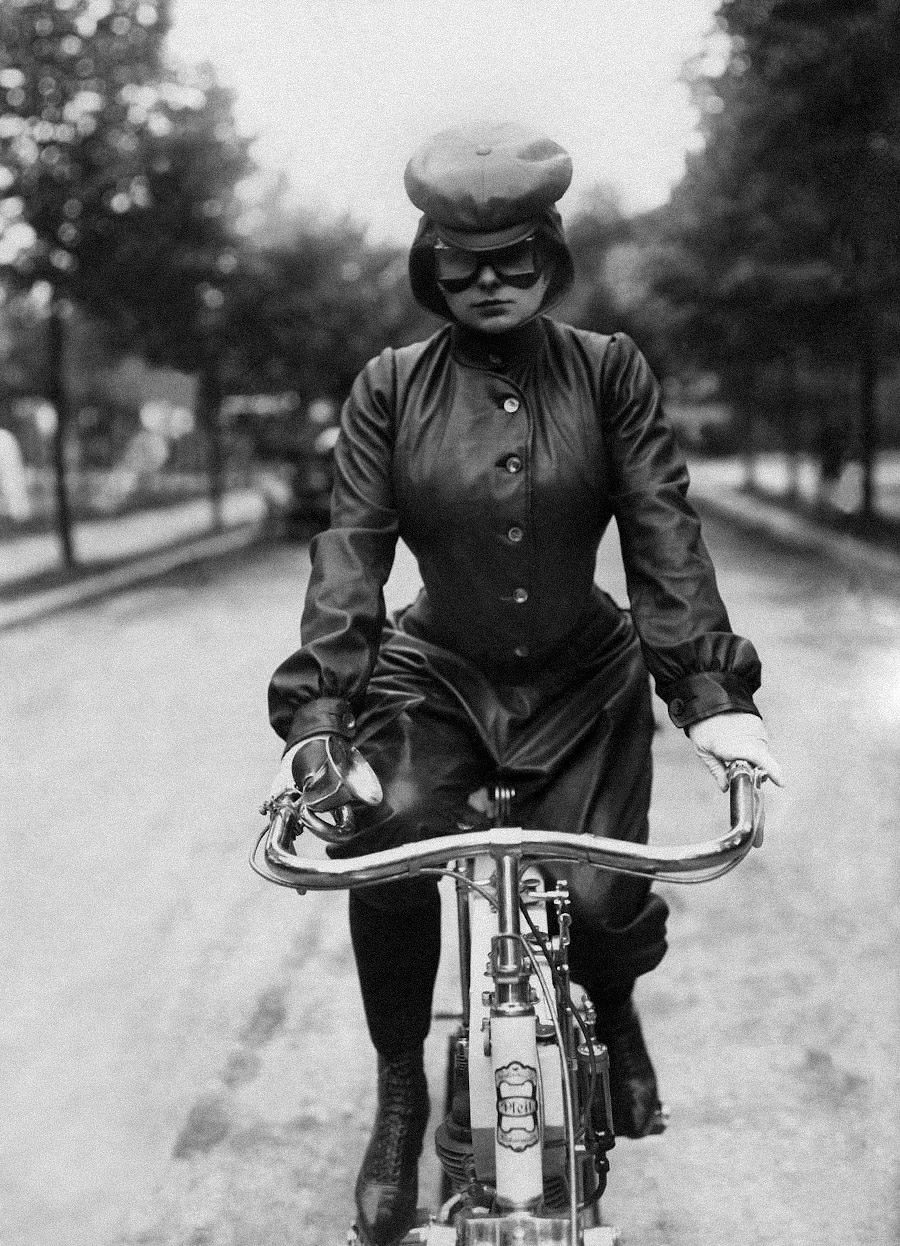

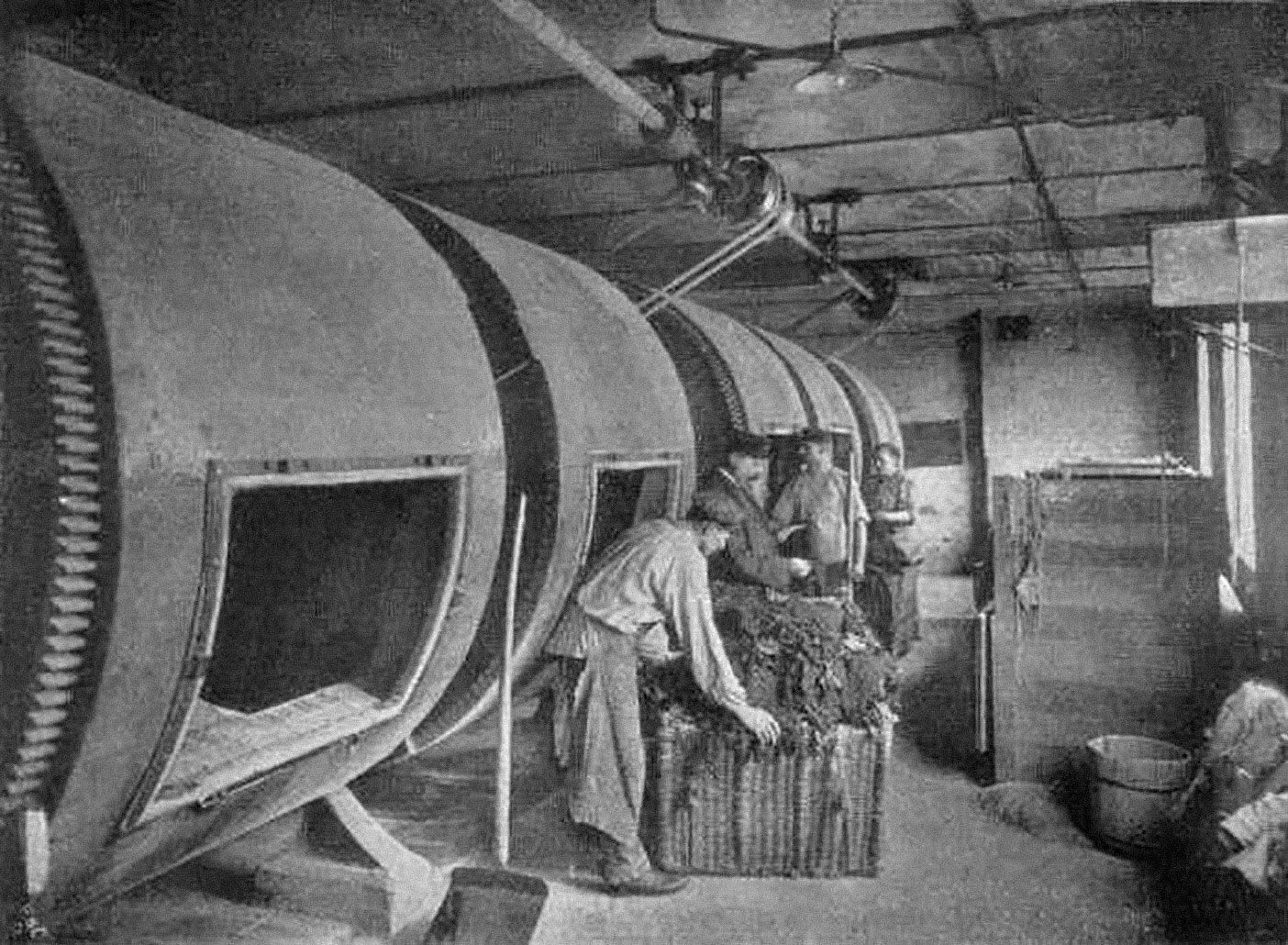

Industrial Revolution

18th - 19th century

The first leather-working machines are introduced. Chemical tanning (chrome tanning, 1858) revolutionizes the sector, making processes faster.

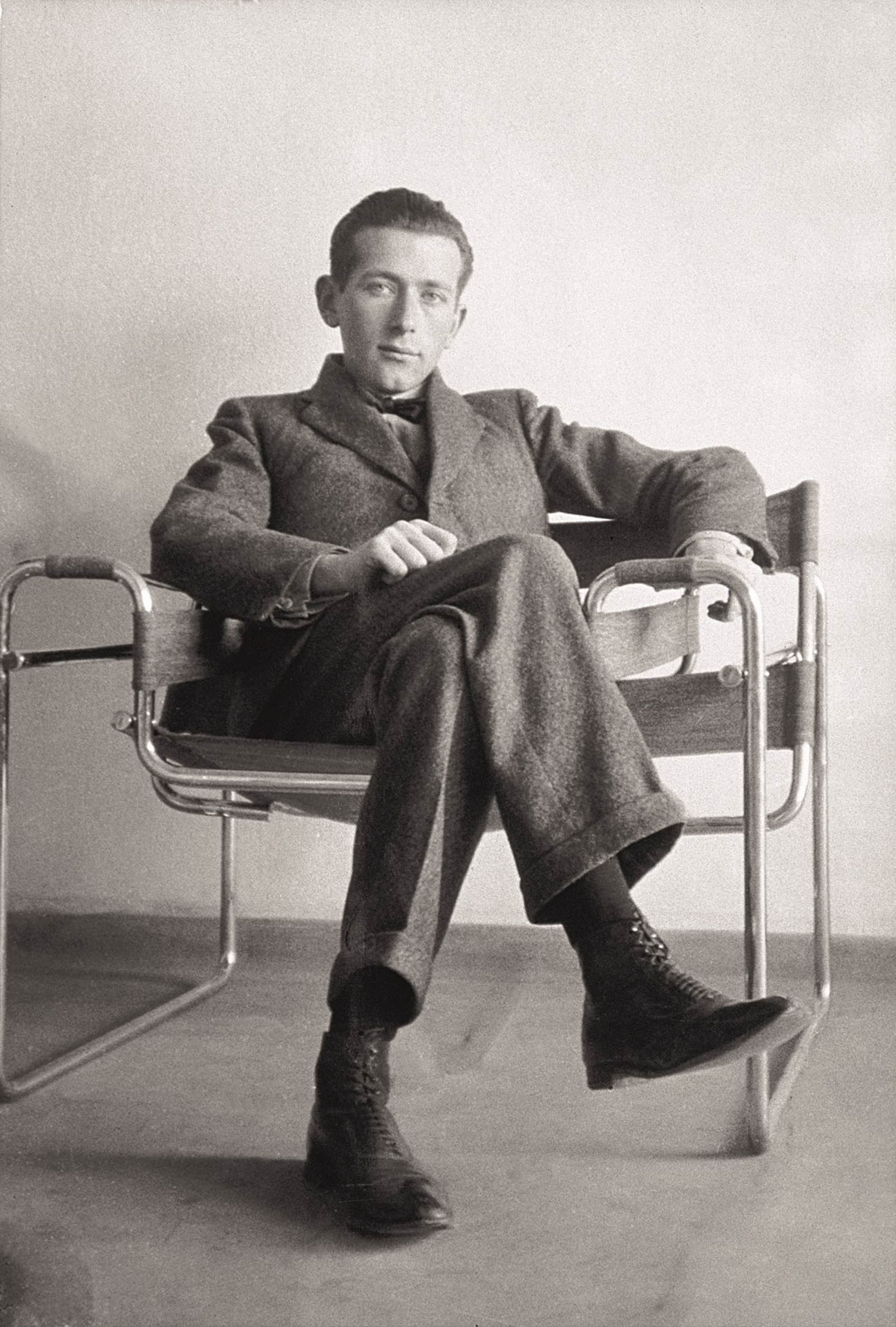

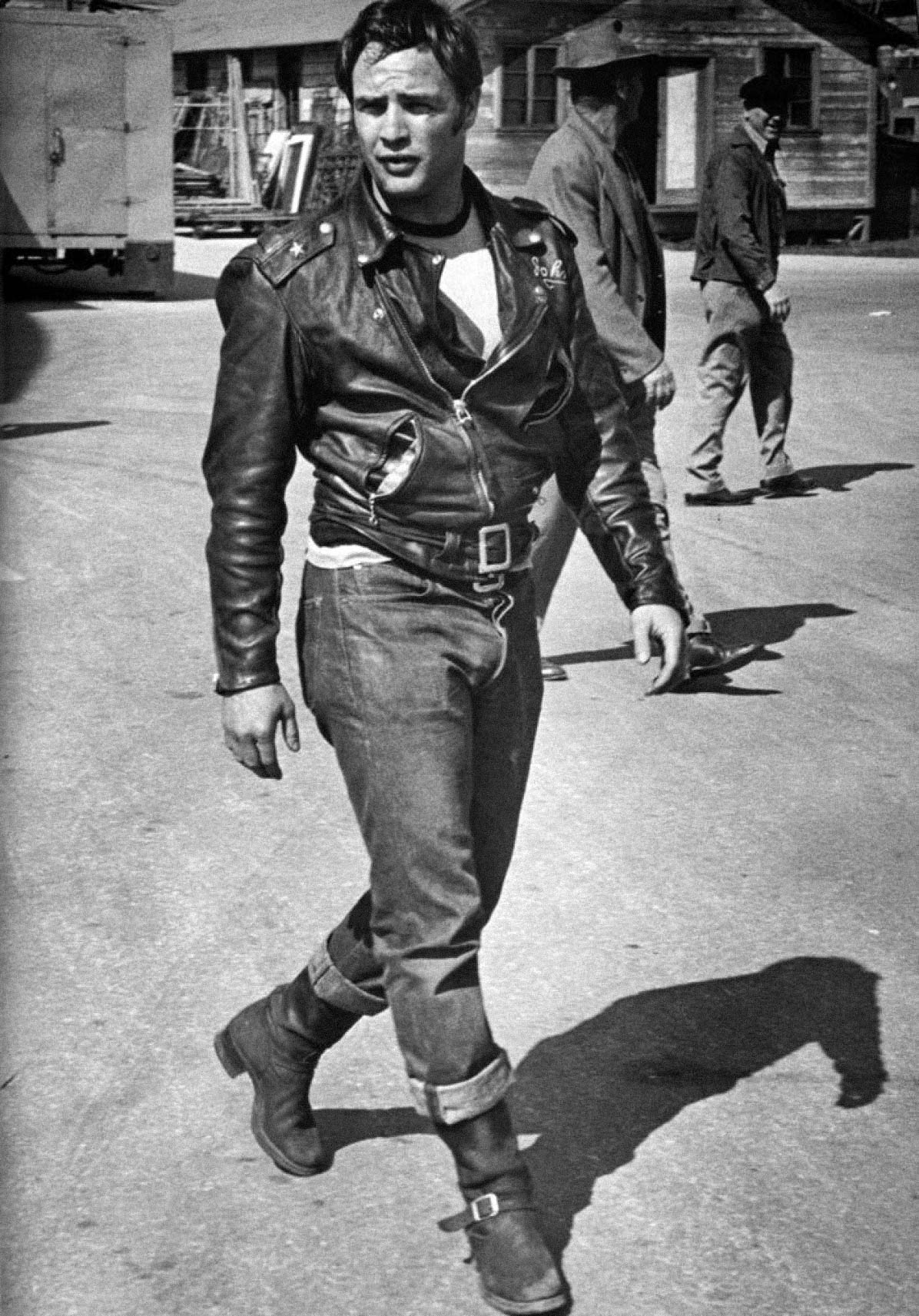

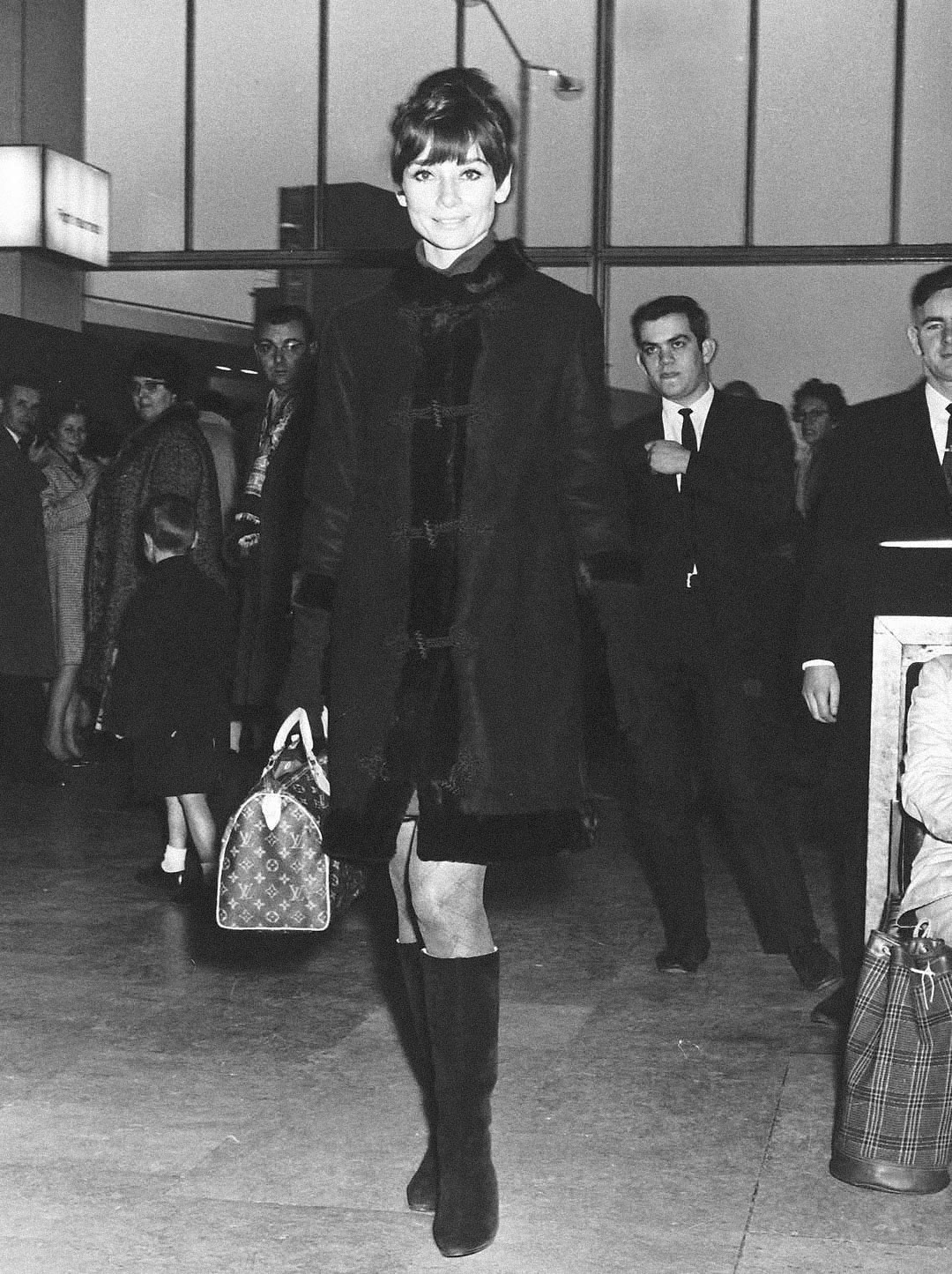

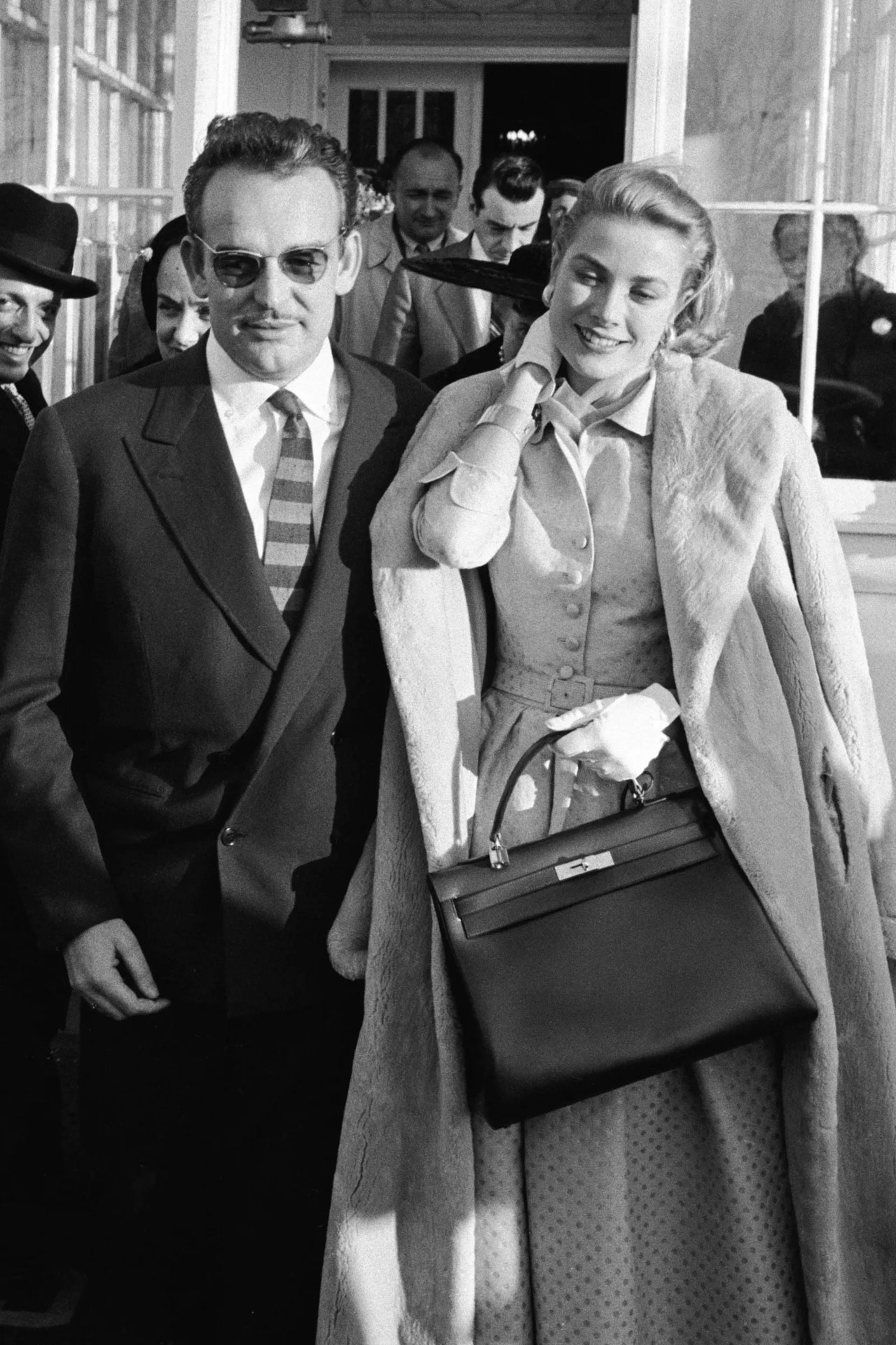

The Twentieth Century

Major fashion and luxury brands arise, using leather for bags, shoes, jackets, and accessories. Design embraces leather, making the material a symbol of status and elegance.

Today

21st century

Attention to sustainability grows. Luxury tanneries invest in green technologies, supply-chain traceability, and environmental certifications, focusing on quality, craftsmanship, and respect for the environment. Conceria del Corso is now an outstanding name in the leather trade. Like the leather it processes, it has evolved and innovated while preserving its authenticity and enhancing the quality of its products. Each manufacturing step is the result of research, expertise, and responsibility: certified processes, care and environmental awareness guarantee its value.

Created

avoiding

waste

And tomorrow?

Eternity is not stillness: it is the ability to regenerate. Leather is a material that weaves together history and innovation, evolving alongside increasingly sustainable technologies that reduce waste and enhance its practical value.